2012 - Sin Tax Law Enacted (RA 10351)

Congress restructured excise taxes on alcohol and tobacco, earmarking a portion of the funds (Sin Tax Collections) for universal healthcare and subsidies to PhilHealth.

2019 - Universal Health Care Act Enacted (RA 11223)

The UHCA was enacted, establishing the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP) with automatic coverage for all Filipinos and defining the specialized "reserve funds" of PhilHealth, mandating that "No portion of the reserve fund or income thereof shall accrue to the general fund of the National Government."

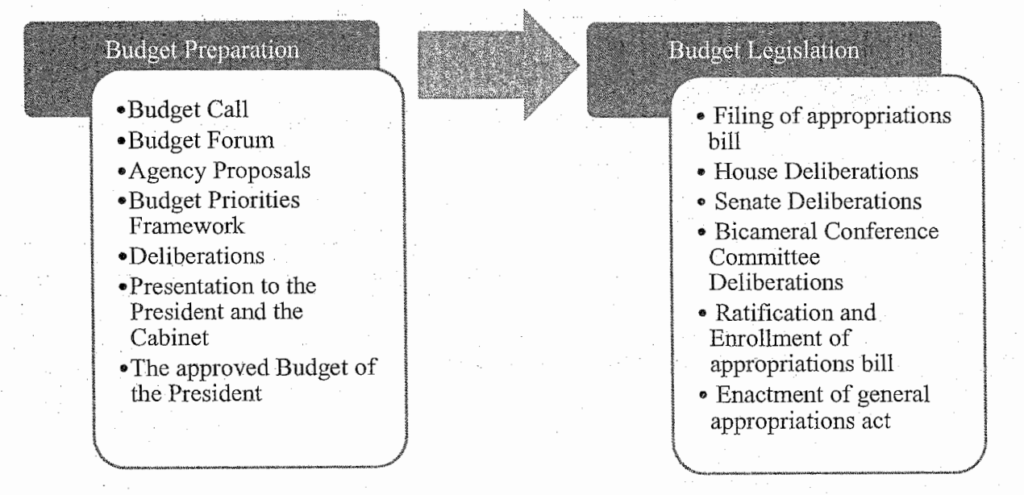

President Submits Budget to Congress

President Marcos, Jr. submitted the Budget of Expenditures and Sources of Financing (BESF) and the National Expenditure Program (NEP) for Fiscal Year (FY) 2024.

President Certifies GAA as Urgent

President Marcos, Jr. certified House Bill No. 8980 (the General Appropriations Bill) as urgent to maintain continuous government operations, dispensing with the three-day printing requirement.

Bicameral Committee Report Approved

The Bicameral Conference Committee (BCC) Report was approved by both Houses, inserting Special Provision 1(d) under the Unprogrammed Appropriations, which mandated the return of the "fund balance" of GOCCs (defined as the remainder after reducing their "reserve funds" to a reasonable level) to the National Treasury.

2024 GAA Signed into Law (RA 11975)

President Marcos, Jr. signed the General Appropriations Act of 2024, including Special Provision 1(d).

2024 GAA Takes Effect

The General Appropriations Act (GAA) of 2024 took effect.

DOF Circular No. 003-2024 Issued

The Department of Finance (DOF) issued the circular implementing Special Provision 1(d), requiring GOCCs like PhilHealth to remit their "fund balance" to the National Treasury.

DOF Orders PhilHealth Remittance

DOF Secretary Ralph Recto instructed PhilHealth to remit its fund balance of PHP 89.9 billion (representing unutilized government subsidies for indirect members from 2021-2023) to the National Treasury.

First Tranche Remitted (PHP 20 Billion)

PhilHealth made the first tranche transfer of PHP 20 billion to the National Treasury.

Second Tranche Remitted (PHP 10 Billion)

PhilHealth made the second tranche transfer of PHP 10 billion.

Third Tranche Remitted (PHP 30 Billion)

PhilHealth made the third tranche transfer of PHP 30 billion, bringing the total remitted amount to PHP 60 billion.

Cases Consolidated; TRO Issued

The Supreme Court consolidated the three petitions (G.R. No. 274778, G.R. No. 275405, and G.R. No. 276233) challenging the constitutionality of the fund transfer.

The Supreme Court issued a Temporary Restraining Order (TRO) against the transfer of the remaining PHP 29.9 billion fund balance.

February 4 & 25, March 4, and April 2 & 3, 2025 - Oral Arguments Held

The Supreme Court consolidated the three petitions (G.R. No. 274778, G.R. No. 275405, and G.R. No. 276233) challenging the constitutionality of the fund transfer.

OSG Submits Motion on Mootness

The Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) submitted a motion to dismiss the petitions for mootness, citing President Marcos, Jr.'s public announcement that the PHP 60 billion remitted would be returned to PhilHealth.

Supreme Court Decision Promulgated

The Supreme Court (En Banc) PARTLY GRANTED the petitions, ruling that:

-

The President's certification of urgency for the 2024 GAA was NOT UNCONSTITUTIONAL.

-

Special Provision 1(d), DOF Circular No. 003-2024, and the PHP 60 billion fund transfer were declared VOID for violating constitutional provisions, including the prohibition on riders and the use of special funds for a purpose other than their creation.

-

The TRO on the remaining PHP 29.9 billion was MADE PERMANENT.

-

The Executive and Legislative branches were ORDERED to include PHP 60 billion as a specific item in the 2026 GAA to be returned to PhilHealth, in addition to its regular budget.

Aquilino Pimentel III, et al. v. House of Representatives, et al. (G.R. No. 274778); Neri Colmenares, et al. v. Executive Secretary Lucas P. Bersamin, et al. (G.R. No. 275405); 1Sambayan Coalition, et al. v. House of Representatives, et al. (G.R. No. 276233)

December 3, 2025

EN BANC

Lazaro-Javier, J.

DOCTRINE:

Special provisions in the General Appropriations Act (GAA) that effect the repeal or amendment of substantive laws, particularly those governing special funds like the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation’s (PhilHealth) “reserve funds,” are void for being unconstitutional riders and for violating the constitutional prohibition against transferring special funds to purposes other than those for which they were created, thereby infringing upon the people’s fundamental right to health and accessible public healthcare.

FACTS:

In 2019, Republic Act No. 11223, or the Universal Health Care Act (UHCA), was enacted, mandating the automatic coverage of every Filipino citizen in the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP) and listing sin tax collections as a primary source of appropriations for its implementation. Section 11 of the UHCA specifically created PhilHealth’s “reserve funds” from accumulated revenues, set an actuarially estimated ceiling for it (two years’ projected expenditures), and strictly prohibited any portion of the reserve fund or its income from accruing to the general fund of the National Government. Furthermore, any excess in these reserves was mandated to be used only to increase benefits and decrease member contributions.

The General Appropriations Act of 2024 (2024 GAA), enacted in December 2023, contained Special Provision 1(d) under Chapter XLIII (Unprogrammed Appropriations). This provision mandated the return to the National Treasury of the “fund balance” of Government-Owned and Controlled Corporations (GOCCs), defined as the remainder resulting from the review and reduction of their “reserve funds” to reasonable levels. By virtue of this provision, the Department of Finance (DOF) issued Circular No. 003-2024, which instructed GOCCs, including PhilHealth, to remit their fund balance. The DOF then directed PhilHealth to remit PHP 89.9 billion, which it labeled as unutilized government subsidies for indirect contributors from 2021 to 2023. PhilHealth, despite having negative total members’ equity when accounting for the Provision for Insurance Contract Liabilities (ICL), remitted PHP 60 billion of this amount in three tranches.

Various petitioners and intervenors, including lawmakers, labor groups, and former government officials, filed petitions for Certiorari and Prohibition assailing the constitutionality of Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular No. 003-2024. They argued, among others, that the special provision was an unconstitutional rider, violated the prohibition against transferring special funds, constituted an invalid delegation of augmentation power, and infringed the people’s constitutional right to health. The Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) defended the provisions, arguing that the PhilHealth “fund balance” was distinct from the legally protected “reserve funds,” that the remittance was justified by PhilHealth’s “idle funds,” and that the issues were non-justiciable.

ISSUE(S):

Are the requisites for a valid exercise of the expanded power of judicial review present?

Is the 2024 GAA unconstitutional for bearing the certification of urgency by the President despite the alleged absence of a public calamity or emergency?

Is Special Provision No. 1(d), as implemented by DOF Circular No. 003-2024, an unconstitutional rider or an inappropriate provision in the 2024 GAA?

Does the transfer of PhilHealth funds to the National Treasury violate the people’s right to health, Section 11 of the UHCA, the Sin Tax Laws, and Article VI, Section 29(3) of the Constitution?

Is the DOF authorized to direct the transfer of savings of GOCCs back to the National Treasury under Article VI, Section 25 of the Constitution?

Does DOF Circular No. 003-2024 violate Section 70 of the 2023 GAA insofar as it orders the transfer of PhilHealth funds the National Treasury before December 30, 2024?

May alleged culpability for technical malversation and/or plunder in the so-called illegal transfer of PhilHealth funds be adjudged in the present cases?

May petitioners properly seek guidelines from the Court on how and when the President may exercise his or her power to certify a bill for immediate enactment?

Assuming that Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular No. 003-2024 are declared unconstitutional, may the Court order the return of the PHP 60 billion PhilHealth funds that have already been transferred to the National Treasury in 2024?

RULING:

1. Are the requisites for a valid exercise of the expanded power of judicial review present?

YES. The Court holds that the four requisites for the exercise of its expanded power of judicial review are all present here.

One. An actual case or controversy exists when there is a conflict of legal rights or an assertion of opposite legal claims between the parties that is susceptible or ripe for judicial resolution. The contrariety of legal rights was satisfied in these cases by the antagonistic or conflicting reasoned positions of the parties vis-à-vis the constitutionality of Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular No. 003-2024. The cases are also ripe for adjudication. As of date, PHP 60 billion of public funds was already remitted to the National Treasury allegedly contrary to the Constitution and other laws. There is therefore a prima facie demonstration of grave abuse of discretion given the reasoned allegations of petitioners that the remittance of these funds is unconstitutional or illegal. The exigencies of the matter at hand render ordinary remedies inadequate.

Two. Locus standi or legal standing is defined as a personal and substantial interest in the case such that the party has sustained or will sustain direct injury as a result of the governmental act that is being challenged. We affirm petitioners’ locus standi. As direct contributors who have consistently paid their premiums to PhilHealth, petitioners stand to be directly and materially injured by the assailed governmental acts which undisputedly affect and involve PhilHealth funds. As beneficiaries of the NHIP, they possess a legal interest in the effective management and utilization of these funds. In any event, the Court may allow suits even if the petitioner fails to show direct injury as the rule on standing is a matter of procedure which can be relaxed when public interest so requires, such as when the matter is of transcendental importance, overarching significance to society, or paramount public interest.

Three. The question of constitutionality was raised at the earliest possible opportunity. In these cases, the constitutionality of the assailed issuances was raised at the earliest opportunity during the lifetime of the 2024 GAA and DOF Circular No. 003-2024 and immediately before their implementation. Thus, the relevant constitutional issues here were raised as soon as the constitutional objections became apparent.

Four. The issue of constitutionality is the very lis mota of the cases. Here, the constitutionality of the contents of, and the procedure for the enactment of, Special Provision 1(d) and the issuance of DOF Circular No. 003-2024 is at issue. The allegations and competing assertions of the parties show that the validity of the assailed issuances cannot be disposed of in any other way except through the constitutional assessment by the Court.

2. Is the 2024 GAA unconstitutional for bearing the certification of urgency by the President despite the alleged absence of a public calamity or emergency?

NO. The president’s act of certifying House Bill No. 8980 and the factual circumstances that caused him to do so do not involve an exercise of judicial, quasi-judicial, or ministerial functions that are ordinarily reviewable under Rule 65. Rather, the President’s decision to certify the bill is a matter of policy which he alone may determine as the chief executive. When the president exercises his or her prerogative under Article VI, Section 26(2) of the Constitution and certifies the immediate enactment of a bill, he or she exercise his or her full and binding discretionary power. For House Bill No. 8980, the president issued the assailed certification because he recognized the importance of the timely passage of the 2024 GAA to sufficiently address the government’s priorities, goals, and needs for the 2024 fiscal year. Between their unsubstantiated claim and the cogent ratiocination posited by the OSG, the latter must prevail. In any event, the only appropriate judge of whether a certification of urgency is proper is the Congress. No one else. Not even the Court, absent any proof that it is tainted with grave abuse of discretion.

We emphasize anew that the Court cannot overrule the wisdom of the president and the wisdom of the Congress and substitute its own. On whether the presidential certification violated the constitutional requirement that printed copies of a bill shall be distributed to members of the Congress in advance before it is subjected to a vote for approval, Tolentino v. Secretary of Finance has long settled that a presidential certification for immediate enactment of a bill dispenses not only with the requirement of reading on three separate days but also the requirement of printing and distribution of printed copies in advance. The phrase “except when the President certifies to the necessity of its immediate enactment, etc.” in Art. VI, § 26(2) qualifies the two stated conditions before a bill can become a law: (i) the bill has passed three readings on separate days and (ii) it has been printed in its final form and distributed three days before it is finally approved. There is, therefore, no merit in the contention that presidential certification dispenses only with the requirement for the printing of the bill and its distribution three days before its passage but not with the requirement of three readings on separate days, also.

3. Is Special Provision No. 1(d), as implemented by DOF Circular No. 003-2024, an unconstitutional rider or an inappropriate provision in the 2024 GAA?

YES. To curb abuses that may be concealed through the voluminous items in an appropriations bill, Article VI, Section 25(2) of the Constitution commands that all provisions of a general appropriations bill must be germane to the purpose of the law. A provision in a general appropriations bill complies with the test of germaneness if it is particular, unambiguous, and appropriate. While it satisfied the requirement of particularity, Special Provision 1(d) is ambiguous. The ambiguity of the subject provision can be gleaned from its introduction of the concept of “fund balance.” First, what is the composition of the so-called “fund balance”? Second, what does “reasonable levels” mean? The existence of these questions suggests a clear conclusion: Special Provision 1(d) is ambiguous. To hit the nail on the head, the DOF was in fact required to issue guidelines to supply the details for the implementation of this provision. Where the law itself is vague, reliance on IRRs to operationalize it is tantamount to an undue delegation of legislative power, as here.

On this score alone, We are already constrained to rule that Special Provision 1(d) is an unconstitutional rider to the 2024 GAA. Still, assuming arguendo that Special Provision 1(d) satisfied the requirement of germaneness, Philippine Constitution Association v. Enriquez identifies which provisions in a general appropriations bill are “inappropriate,” thus, must be struck down: provisions which are intended to amend other laws, because clearly these kinds of laws have no place in an appropriations bill. In Gov. Mandanas v. Hon. Romulo, We emphasized that the Congress is not allowed to amend statutes through a general appropriations law but must enact a separate law for such amendment. Here, We find that Special Provision 1(d) is equally infirm because it amended the provisions of the UHCA and the Sin Tax Laws.

4. Does the transfer of PhilHealth funds to the National Treasury violate the people’s right to health, Section 11 of the UHCA, the Sin Tax Laws, and Article VI, Section 29(3) of the Constitution?

YES. As set forth in the first paragraph of Section 11 of the UHCA, PhilHealth derives its “reserve funds” from a portion of PhilHealth’s accumulated revenues less their current year expenditures. The total “reserve funds” includes the contributions of both direct and indirect members, government subsidies, and the income arising from investing unused portions of the “reserve funds.” Section 11 of the UHCA, in no equivocal terms, further commands that “no portion of the reserve fund or income thereof shall accrue to the general fund of the National Government or to any of its agencies or instrumentalities, including GOCCs.” This restriction is based on sound public policy. The “reserve funds” of PhilHealth is a restricted fund earmarked for two purposes vital to the existence and viable and sustainable operations of PhilHealth as a public health insurer: first, to answer for the urgent yet unexpected obligations of PhilHealth and NHIP as they fall due, ensuring that PhilHealth as a public health insurer continues as a going concern; and second, to generate sufficient funds to expand and elevate the goods and services, inclusive of premium contributions, that PhilHealth can viably provide to our people. Special Provision 1(d) invariably refers to the GOCC’s “reserve funds” when deriving the “fund balance.” In his interpellation, Justice Caguioa was able to confirm from the solicitor general that the “fund balance” was obtained by DOF from the PHP 183.1 billion difference between the PHP 464.26 billion “reserve funds” and the DOF-imposed ceiling of PHP 280.1 billion. In other words, the PHP 89.9 billion “unutilized” government subsidies of PhilHealth for years 2021 to 2023 formed part of its surplus or net income, which PhilHealth, in turn, transferred at the end of every fiscal year to form part of its “reserve funds” for the following year. This surplus or net income has long assumed the nature of restricted funds of PhilHealth as “reserve funds” under Section 11 of the UHCA prior to the implementation of Special Provision 1(d). The incompatibility between Special Provision 1(d) and its implementing DOF Circular No. 003-2024, on one hand, and Section 11 of the UHCA, on the other, rendered them irreconcilable and incapable of simultaneous compliance.

First. The DOF used an averaging method in place of the actuarial computation required by Section 11 of the UHCA when the DOF computed and imposed the PHP 280.6 billion ceiling. By doing so, Special Provision 1(d), as implemented by DOF Circular No. 003-2024, completely covers the subject of Section 11 of the UHCA and substituted or repealed, or at the very least, amended this provision by disregarding the other factors relevant to PhilHealth’s current and future operations when it simplistically limited the computation of the ceiling to the past and, possibly, already obsolete historical financial data of PhilHealth.

Second. Assuming for the sake of argument that the PHP 280.6 billion ceiling imposed by the DOF was correct and the “reserve funds” of PhilHealth in 2023 amounted to PHP 464.28 billion, the balance of PHP 183.1 billion is still the difference between the “reserve funds” and the ceiling for the “reserve funds,” which then makes this balance the excess “reserve funds” of PhilHealth. Under Section 11 of the UHCA, when the “reserve funds” exceeds the ceiling, as in the computation provided by the OSG and the DOF, the excess “reserve funds” shall be devoted only to two specific purposes and no other: one, to increase the benefits under the NHIP; and two, to decrease the contributions of members. Therefore, when Special Provision 1(d) diverted the use of these excess “reserve funds” to fund the projects and programs under the Unprogrammed Appropriations of the 2024 GAA, Special Provision 1(d) set aside or substituted or repealed or, at the very least, amended Section 11 of the UHCA by: 1. directly replacing the purposes under Section 11 to which the excess “reserve funds” of PhilHealth is mandatorily devoted; and 2. directly putting in place a mechanism that recharacterizes the “reserve funds” as unrestricted “fund balance,” which can then be literally taken out of PhilHealth and the NHIP and away from their mandatory intended purposes – both contrary to Section 11.

Third. The Sin Tax Laws are intended not only to curb excessive consumption of substances or goods that are detrimental to the health of people, but also to raise revenue for the implementation of the UHCA. The relevant percentages of sin tax collections as set forth in the amended Section 288-A of the NIRC “shall be allocated and used exclusively” for, among others, the implementation of the UHCA. It is beyond question, therefore, that sin tax collections, subsequently remitted to PhilHealth in the form of premiums of indirect contributors, are special funds allotted for a specific purpose. Article VI, Section 29(3) of the Constitution is unequivocal: “All money collected on any tax levied for a special purpose shall be treated as a special fund and paid out for such purpose only.” Article VI, Section 29 (3) of the Constitution admits of only one exception for the transfer of special funds to the general fund of the National Government, i.e., if the purpose for which a special fund was created has been fulfilled or abandoned. The constitutional mandate is clear. As long as the legislative purpose endures, so too must the integrity and exclusivity of the funds committed to it persist chronically. Hence, when Special Provision 1(d) diverted the use of the PhilHealth “reserve funds” that were sourced from these earmarked excise taxes to fund instead the programs and projects under the Unprogrammed Appropriations of the 2024 GAA, Special Provision 1(d) clearly and convincingly repealed the categorical mandatum of the Sin Tax Laws to limit the use of the excise tax percentages for funding the UHCA and directly contravened the prohibition enshrined in Article VI, Section 29(3) of the Constitution.

Fourth. This financial misalignment is not merely a budgeting error—it is a breach of our constitutionally guaranteed right to health. The diversion of PhilHealth resources undermines the UHCA’s legal architecture and violates the constitutional obligation to strive toward equitable, affordable, and sustainable health services for all. The transfer of funds from PhilHealth is “fundamentally disruptive to the UHCA’s framework,” undermining the mechanism by which the State meets its healthcare obligations and threatening the universal healthcare system. The government does not have the prerogative to rank national projects at the cost of undermining a constitutionally guaranteed right, especially when the prioritization of these other projects rests on false invocations of “urgency” and lack of funding. In this context, Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular No. 003-2024, insofar as they mandated the transfer of PhilHealth’s “reserve funds” to the National Treasury, constitute a direct and indefensible breach of the right to health.

5. Is the DOF authorized to direct the transfer of savings of GOCCs back to the National Treasury under Article VI, Section 25 of the Constitution?

NO. Article VI, Section 25(5) of the Constitution defines the power of augmentation: “No law shall be passed authorizing any transfer of appropriations; however, the President, the President of the Senate, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and the heads of Constitutional Commissions may, by law, be authorized to augment any item in the general appropriations law for their respective offices from savings in other items of their respective appropriations.”

The power to transfer savings under Article VI, Section 25(5) of the Constitution pertains to the president, the president of the senate, the speaker of the House of Representatives, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, and the heads of Constitutional Commissions—the list is exclusive and signifies no other. As held in Philippine Constitution Association v. Enriquez, while Article VI, Section 25(5) of the Constitution allows as an exception to the realignment of savings to augment items in the general appropriations law for the executive branch, this power must and can be exercised only by the President alone, pursuant to a specific law. In fine, the secretary of finance cannot, in any capacity whether as alter ego of the president or as head of department, exercise the power of augmentation under the Constitution. The funds transferred were not “savings” generated from the appropriations for the Office of the President.

In Araullo v. Aquino, the Court stressed that “savings” must come from the appropriations of the augmenting office itself. Neither is the “fund balance” from the appropriations of the Office of the President, having been derived from the “reserve funds” of PhilHealth. The transfer here was not made to augment an item in the general appropriations law for the Office of the President. The funds were not also intended for PhilHealth to augment its own appropriations. What cannot be done directly cannot be done indirectly. While the form may differ from direct augmentation under Article VI, Section 25(5) of the Constitution, the result is the same: funds appropriated to PhilHealth are redirected and repurposed for the use of other budget items, here, Unprogrammed Appropriations. This set-up attempts to side-step but brazenly infringes the prohibition against the cross-border transfer of funds—that is, moving funds across institutional boundaries—and violates the proscription on the realignment of funds that have already been specifically appropriated.

6. Does DOF Circular No. 003-2024 violate Section 70 of the 2023 GAA insofar as it orders the transfer of PhilHealth funds the National Treasury before December 30, 2024?

NO. While the remittance of excess funds may have been in line with the cash budgeting system that discourages accumulation of unused obligations or idle funds for efficient cash management, the nature of the funds of PhilHealth precludes the application of the cash budgeting system. As exhaustively discussed, the funds of PhilHealth are special funds created for a special purpose contemplated under Article VI, Section 29(3) of the Constitution. Hence, the cash budgeting system finds no application to the remittance of PhilHealth funds as there can be no instance that its funds will remain unobligated. While its funds may be unspent at a given time, there will still be no unobligated funds to speak of, as they are exclusively appropriated for the people’s right to health.

7. May alleged culpability for technical malversation and/or plunder in the so-called illegal transfer of PhilHealth funds be adjudged in the present cases?

NO. A petition for certiorari and prohibition—a special civil action limited to a determination of grave abuse of discretion—is not the proper remedy to adjudge criminal liability or innocence for technical malversation or plunder. The only issue to be adjudicated here is the constitutionality of the assailed issuances and whether they were tainted with grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction.

8. May petitioners properly seek guidelines from the Court on how and when the President may exercise his or her power to certify a bill for immediate enactment?

NO. The Court declines to heed the prayer of Atty. Colmenares et al. to issue guidelines on the president’s exercise of his or her privilege to certify to the immediate enactment of a bill under Article VI, Section 26(2) of the Constitution. The desired guidelines are superfluous, if not inappropriate. The Constitution is clear on when and why this certification is issued by the president. Too, the Congress is the sole judge of the sufficiency and propriety of the urgency certification by the president.

9. Assuming that Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular No. 003-2024 are declared unconstitutional, may the Court order the return of the PHP 60 billion PhilHealth funds that have already been transferred to the National Treasury in 2024?

YES. As a consequence of the unconstitutional transfer of the subject PhilHealth funds to the National Treasury pursuant to Special Provision 1(d) of the 2024 GAA and DOF Circular 003-2024, the remitted funds amounting to PHP 60 billion to PhilHealth must be returned to the coffers of PhilHealth. The operative fact doctrine is a rule of equity. As such, it must be applied as an exception to the general rule that an unconstitutional law produces no effects. It can never be invoked to validate as constitutional an unconstitutional act. Here, the nature of the funds taken from PhilHealth warrants the application of the general rule. What is at stake is the cost of protecting the lives and health of the people. It diminished the resources that were exclusively reserved for the implementation of the UHCA—crippling the State’s capability to deliver preventive, promotive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative care for medical, dental, mental and emergency health services. To rule otherwise would have far more detrimental and far-reaching consequences. It cannot be emphasized enough that this involves no less than the right to health of the people. Depriving the people of these funds when the implementation of the universal healthcare is still in its critical early stages is tantamount to the abandonment by the State of its duty to uphold this inviolable right. The retention of the special fund constitutes a continuing violation of the people’s right to health. Thus, the return of the PHP 60 billion funds to PhilHealth is proper.

Republic of the Philippines

Supreme Court

Manila

EN BANC

AQUILINO PIMENTEL III; ERNESTO OFRACIO; JANICE LIRZA D. MELGAR; MARIA CIELO MAGNO; MA. DOMINGA CECILIA B. PADILLA; DANTE M. GATMAYTAN; IBARRA B. GUTIERREZ; SENTRO NG MGA NAGKAKAISA AT PROGRESIBONG MANGGAGAWA; PUBLIC SERVICES LABOR INDEPENDENT CONFEDERATION FOUNDATION, INC.; and PHILIPPINE MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, Petitioners,

ATTY. JOSE SONNY MATULA, President of the Federation of Free Workers (FFW-NAGKAISA LABOR COALITION); DANIEL EDRALIN, Secretary General, National Union of Workers in Hotel Restaurant and Allied Industries (NUWHRAIN-NAGKAISA); RENATO MAGTUBO, Chairperson, Partido Manggagawa (PM-NAGKAISA); JULIUS A. CAINGLET, Co-Convenor, CHURCH-LABOR CONFERENCE, GRACE ESTRADA, President, Pinay Careworkers Transnational (PIN@Y); ALFREDO MARANAN, FFW National Treasurer; JUN RAMIREZ MENDOZA, Union President, Vishay Employees Philippines Union-FFW and National Vice President, FFW; JUDY ANN CHAN MIRANDA, Chairperson, Nagkaisa Women Committee and General Secretary, PM-NAGKAISA; VILMA G. REYES, Union President, Dela Salle Medical and Health Sciences Institute Employees Union-FFW, National Board Member, FFW; RENE L. CAPITO, National President, Alliance of Filipino Workers (AFW); ELIJA R. SAN FERNANDO, National Vice President, National Federation of Labor (NFL); RENE DE MESA TADLE, President of the Council of Teachers and Staff of Colleges and Universities of the Philippines (CoTeSCUP); EMERITO C. GONZALES, Union President UST Faculty Union (USTFU); DENNIES GUTIERREZ, Union President, Interphil Laboratories Employees Union-FFW (ILEU-FFW); ROLANDO LIBROJO, Convenor, Kilusang Artikulo 13 (A.13); and ATTY. DANILO C. ISIDERIO, FFW Legal Center, Petitioners-in-Intervention,

v.

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES represented by the Speaker Ferdinand Martin Romualdez; SENATE OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES, represented by SENATE PRESIDENT FRANCIS ESCUDERO; DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE SECRETARY RALPH RECTO; EXECUTIVE SECRETARY LUCAS BERSAMIN; and PHILIPPINE HEALTH INSURANCE CORPORATION represented by its President, Emmanuel R. Ledesma, Jr.

[ G.R. No. 274778, December 3, 2025]

BAYAN MUNA CHAIRMAN NERI COLMENARES, BAYAN MUNA VICE CHAIRMAN TEODORO A. CASIÑO, BAYAN MUNA EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT CARLOS ISAGANI T. ZARATE, and FORMER BAYAN MUNA REPRESENTATIVE FERDINAND R. GAITE

v.

EXECUTIVE SECRETARY LUCAS P. BERSAMIN, SENATE OF THE PHILIPPINES and THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

[ G.R. No. 275405]

1SAMBAYAN COALITION; MEMBERS OF U.P. LAW CLASS 1975 namely: JOSE P.O. ALILING IV, AUGUSTO H. BACULIO, EDGARDO R. BALBIN, MOISES B. BOQUIA, ANTONIO T. CARPIO, MANUEL C. CASES, JR., RICHARD J. GORDON, OSCAR L. KARAAN, BENJAMIN L. KALAW, LUCAS C. LICERIO, TOMAS N. PRADO, ELIZER A. ODULIO, OSCAR M. ORBOS, AURORA A. SANTIAGO, EMILY SIBULO-HAYUDINI, CONRAD D. SORIANO, and JOSE B. TOMIMBANG; FORMER OMBUDSMAN CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES; SENIOR FOR SENIORS ASSOCIATION, INC., represented by MS. CAROL BLANCO BENAVIDES; KIDNEY FOUNDATION OF THE PHILIPPINES, represented by ATTY. VICENTE GREGORIO; and ATTY. CHRISTOPHER JOHN P. LAO

v.

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES represented by the speaker, FERDINAND MARTIN ROMUALDEZ; THE SENATE OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES represented by the Senate President FRANCIS JOSEPH ESCUDERO; DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE SECRETARY RALPH RECTO; EXECUTIVE SECRETARY LUCAS BERSAMIN; and PHILIPPINE HEALTH INSURANCE CORPORATION, represented by its President, EMANNUEL R. LEDESMA, JR.

[ G.R. No. 276233]

DECISION

LAZARO-JAVIER, J.:

PREFATORY

Health is wealth, but wealth is also health.

In the Philippines, the age-old adage health is wealth is not just wisdom—it is a warning. When 42.7% of healthcare expenses are paid directly out of pocket by Filipino families,1 a painful truth emerges: wealth is health. And for too many, this truth decides whether life proceeds with dignity or spirals into debt, despair, and suffering.

Consider a story recently aired on national television:2 A father—working-class and devoted—suffered a stroke worsened by diabetes. His leg was amputated. The hospital bill reached PHP 400,000.00. Even after discounts, his family was short by PHP 65,000.00. They borrowed money to be able to pay, and debt began its cruel descent. But the costs did not end at discharge. Medications, therapy, and home adjustments followed. Unable to cope, they rationed his prescriptions. Not out of neglect, but necessity. Their budget left no other option.

This is not an isolated tragedy. It echoes across thousands of Filipino households—unheard, unseen, but no less real. It forces us to confront a chilling contradiction: What good is a constitutionally guaranteed right to life when the right to health remains financially unreachable?

A deafening silence looms between law and lived reality.

The right to health is not abstract philosophy. It is the heartbeat of the right to life—the foundation on which all other freedoms stand. It is primus inter pares—first among equals—in the constellation of rights that uphold human dignity.

Illness does not strike in isolation. It devours entire families. It robs children of opportunity, breadwinners of strength, and communities of resilience. Without health, our capacity to work, learn, vote, protest, parent, or even survive erodes. And with it, so does our ability to claim the other rights we hold dear.

This is why the right to health is not merely important. It is enabling, elevating, empowering. A government that protects this right affirms the value of every human life. It anchors dignity in policy. It puts compassion into practice.

But rights need resources. We fund our courts to defend liberty. We support education to unlock potential. We invest in national defense to preserve peace. Yet health is persistently underfunded—a paradox given how foundational it is. Why does the most immediate right remain the most neglected?

To remain silent is to remain complicit.

Those who are sick may not storm the halls of power, but their struggles must command equal urgency. Their pain is enduring. Their care must be treated as a core pillar of justice. Their quiet suffering demands loud, unwavering advocacy.

The Judiciary has a constitutional mandate: To protect not only the abstract right to health, but the concrete right to accessible, affordable, and sustainable public healthcare. The Universal Health Care Act (UHCA) is a landmark step. It speaks of inclusion, protection, and equity. But laws are only as strong as the commitment behind them. And commitment needs funding, structure, empathy, and vigilance.

We must demand a system that heals—then supports, prevents, and uplifts. Because when health becomes a privilege, life itself becomes a commodity. And in any society worthy of justice, neither should it ever be for sale.

Health is never abstract or theoretical. It is intimate. Immediate. Non-negotiable. It must be safeguarded—not eventually, not someday, not 10 years after, but today.

A healthy population is not just the bedrock of national development; it is the highest expression of our shared humanity. When our people are protected by a just and reliable health system, we do more than survive. We thrive. We dream. We hope.

The Cases

These three consolidated Petitions for Certiorari and Prohibition3 and Petition-in-Intervention4 assail for being unconstitutional Special Provision 1(d), Chapter XLIII of Republic Act No. 11975 [Special Provision 1(d)] or the General Appropriations Act of 2024 (2024 GAA) and Department of Finance (DOF) Circular No. 003-2024 (DOF Circular No. 003-2024) which mandated the transfer to the National Treasury of PHP 89.9 billion representing the “fund balance” of the Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth).

Antecedents

In 2012, Congress enacted Republic Act No. 103515 which restructured the excise tax on alcohol and tobacco products. It earmarked funds for universal healthcare and covered the subsidies of the National Government to the premium contributions of indigents or indirect contributors under the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP). Subsequently, Republic Act No. 10351 was amended to include excise tax on heated tobacco and vapor products.6 These taxes have since become the primary component of the government subsidy received by PhilHealth annually pursuant to Section 87 of Republic Act No. 10351, as amended.

In 2019, Republic Act No. 11223 or the UHCA8 was enacted, expanding the country’s social health insurance.9 Consistent with Republic Act No. 10351 as amended, Section 37 of the UHCA listed total incremental sin tax collections as one of the sources of appropriations for the implementation of the NHIP:

Section 37. Appropriations. The amount necessary to implement this Act shall be sourced from the following:

(a) Total incremental sin tax collections as provided for in Republic Act No. 10351, otherwise known as the “Sin Tax Reform Law:” Provided, That the mandated earmarks as provided for in Republic Act Nos. 7171 and 8240 shall be retained;

(b) Fifty percent (50%) of the National Government share from the income of the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation as provided for in Presidential Decree No. 1869, as amended: Provided, That the funds raised for this purpose shall be transferred to PhilHealth at the end of each quarter subject to the usual budgeting, accounting and auditing rules and regulations; Provided, further, That the funds shall be used by PhilHealth to improve its benefit packages;

(c) Forty percent (40%) of the Charity Fund, net of Documentary Stamp Tax Payments, and mandatory contributions of the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (PCSO) as provided for in Republic Act No. 1169, as amended: Provided, That the funds raised for this purpose shall be transferred to PhilHealth at the end of each quarter subject to the usual budgeting, accounting, and auditing rules and regulations; Provided, further, That the funds shall be used by PhilHealth to improve its benefit packages;

(d) Premium contributions of members;

(e) Annual appropriations of the Department of Health (DOH) included in the GAA; and

(f) National Government subsidy to PhilHealth included in the GAA.

The amount necessary to implement the provisions of this Act shall be included in the GAA and shall be appropriated under the DOH and National Government subsidy to PhilHealth, the DOH, in coordination with PhilHealth, may request Congress to appropriate supplemental funding to meet targeted milestones of this Act. (Emphasis supplied)

The UHCA also provided a 10-year implementation period.10 Section 5 ordained the automatic coverage of every Filipino citizen in the NHIP while Section 6 enumerated the health care services that must be granted to every Filipino citizen, thus:

Section 5. Population Coverage. Every Filipino citizen shall be automatically included into the NHIP, hereinafter referred to as the Program.

Section 6. Service Coverage. –

(a) Every Filipino shall be granted immediate eligibility and access to preventive, promotive, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative care for medical, dental, mental and emergency health services, delivered either as population-based or individual-based health services: Provided, That the goods and services to be included shall be determined through a fair and transparent [Health Technology Assessment (HTA)] process;

(b) Within two (2) years from the effectivity of this Act, PhilHealth shall implement a comprehensive outpatient benefit, including outpatient drug benefit and emergency medical services in accordance with the recommendations of the Health Technology Assessment Council (HTAC) created under Section 34 hereof;

(c) The DOH and the local government units (LGUs) shall endeavor to provide a health care delivery system that will afford every Filipino a primary care provider that would act as the navigator, coordinator, and initial and continuing point of contact in the health care delivery system; Provided, That except in emergency or serious cases and when proximity is a concern, access to higher levels of care shall be coordinated by the primary care provider; and

(d) Every Filipino shall register with a public or private primary care provider of choice. The DOH shall promulgate the guidelines on the licensing of primary care providers and the registration of every Filipino to a primary care provider.

In 2020, Section 14 of Republic Act No. 1134611 further inserted a new provision, Section 288-A, under Chapter II, Title XI of the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC), which reserved a portion of the revenues from excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages, alcohol products, tobacco products and heated tobacco and vapor products (sin tax) for the implementation of the UHCA.

Finally, Section 9 of Republic Act No. 1146712 amended Section 288-A of the NIRC, increasing the portion of the excise or sin taxes reserved for the implementation of the UHCA.

On August 2, 2023, President Ferdinand R. Marcos, Jr. (President Marcos, Jr.) submitted to the Congress the following documents relating to the national budget for the fiscal year 2024: (a) Budget Message;13 (b) Budget of Expenditures and Sources of Financing (BESF);14 (c) National Expenditure Program (NEP);15 and (d) Staffing Summary.16

On August 30, 2023, members of the House of Representatives filed House Bill No. 8980 titled “An Act Appropriating Funds for the Operation of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines from January One to December Thirty-One, Two Thousand and Twenty-Four.”$^{17}$

House Bill No. 8980 adopted the PHP 5.7676 trillion budget, with PHP 4.0198 trillion programmed appropriations, PHP 1.7478 trillion automatic appropriations, and PHP 281.9 billion unprogrammed appropriations, as recommended by President Marcos, Jr. in his budget submissions.

On September 4, 2023, House Bill No. 8980 was tackled on First Reading in the House of Representatives. By Letter dated September 20, 2023 addressed to Speaker Ferdinand Martin G. Romualdez of the House of Representatives (Speaker Romualdez), President Marcos, Jr. certified as urgent House Bill No. 8980.

On September 27, 2023, House Bill No. 8980 was approved by the House of Representatives on Second and Third Readings. The approved version of House Bill No. 8980 was transmitted to the Senate for its concurrence on November 4, 2023,$^{18}$ and tackled on First Reading in the Senate on November 6, 2023.

On November 28, 2023, the Senate approved House Bill No. 8980 on Second Reading with amendments and, on the same day, House Bill No. 8980 was approved by the Senate on Third Reading.19

The Senate and the House of Representatives thereafter designated their conferees to the Bicameral Conference Committee (BCC) to tackle specific provisions of House Bill No. 8980 on which the Houses of Congress did not agree. The BCC held two meetings for this purpose, first on November 28, 2023, and second on December 6, 2023.20

On December 11, 2023, the BCC submitted its Report to both the House of Representatives and the Senate, recommending the approval of House Bill No. 8980 which: first, reflected an increase in the amount of unprogrammed appropriations from PHP 281.9 billion to PHP 731.4 billion; and second, inserted Special Provision 1(d) under Chapter XLIII on unprogrammed appropriations, ordaining the return to the National Treasury of “the fund balance of government-owned and controlled corporations (GOCCs) from any remainder resulting from the review and reduction of their ‘reserve funds’ to reasonable levels taking into account the disbursement from prior years.”

On the same day, the Report was approved by both Houses of Congress.21

On December 20, 2023, the President signed House Bill No. 8980 into law, now known as Republic Act No. 11975 or the 2024 GAA.22 It took effect on January 1, 2024.23 Special Provision 1(d) thereof under Chapter XLIII on unprogrammed appropriations authorized the return of the “fund balance” or the excess “reserve funds” of GOCCs to the National Treasury to fund unprogrammed appropriations under the 2024 GAA, viz.:24

Special Provision(s)

1. Availment of the Unprogrammed Appropriations. The amounts authorized herein for Purpose Nos. 1, 3-5, and 7-51 may be used when any of the following exists:

…….

(d) Fund balance of the Government-Owned or -Controlled Corporation (GOCCs) from any remainder resulting from the review and reduction of their reserve funds to a reasonable levels taking into account disbursement from prior years.

The Department of Finance shall issue the guidelines to implement this provision within fifteen (15) days from effectivity of this Act. (Emphasis supplied)

By virtue of this provision, the DOF issued DOF Circular No. 003-2024 on February 27, 2024, requiring GOCCs such as PhilHealth to remit their fund balance to the National Treasury, thus:25

Section 5. PROCEDURE FOR THE COLLECTION AND REMITTANCE OF FUND BALANCE

1. The DOF shall notify in writing the GOCC regarding the Fund Balance to be remitted to the Bureau of the Treasury (BTr). The date of the electronic transmission shall be considered as the date of receipt.

2. The GOCC shall remit to the BTr the Fund Balance within fifteen (15) calendar days from the receipt of such notice. Upon remittance, the GOCC shall inform the DOF of such remittance including the proof thereof.

3. Upon remittance, the BTr shall issue to the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) a certification stating the amount of the Fund Balance remitted to the BTr by the GOCC in accordance with these Guidelines and copy furnishing DOF. The certification shall become the basis of the DBM in the release of funds chargeable against unprogrammed appropriations under Republic Act No. 11975, subject to applicable budgeting, accounting and auditing rules and regulations.

4. Any remitted Fund Balance shall not be considered as a payment of any dividend arrears or advance dividend payment for the succeeding dividend years pursuant to Republic Act No. 7656, entitled as “An Act Requiring Government-Owned Or-Controlled Corporations To Declare Dividends Under Certain Conditions To The National Government, And For Other Purposes.” (Emphasis supplied)

Under Letter26 dated April 24, 2024, Secretary Ralph G. Recto (Secretary Recto) of the DOF instructed PhilHealth to remit to the National Treasury its fund balance of PHP 89 billion, later clarified to be PHP 89.9 billion. These funds were supposedly the excess “reserve funds” of PhilHealth coming from the government subsidy contributions or premiums for indigents or indirect contributors which it received for the years 2021, 2022, and 2023.27

In compliance, the PhilHealth Board of Directors approved the transfer of the subject funds, and remitted PHP 20 billion to the National Treasury for the first tranche on May 10, 2024;$^{28}$ PHP 10 billion on August 21, 2024 for the second tranche;$^{29}$ and PHP 30 billion on October 16, 2024 for the third tranche.29

On September 20, 2025, President Marcos, Jr. announced that the PHP 60 billion fund balance of PhilHealth remitted to the National Treasury will be returned to the PhilHealth.30

The Present Petitions

G.R. No. 274778

Petitioners Senator Aquilino Pimentel III, Ernesto Ofracio, Junice Lirza D. Melgar, Maria Cielo Magno, Ma. Dominga Cecilia B. Padilla, Dante B. Gatmaytan, Sentro ng mga Nagkakaisa at Progresibong Manggagawa, Inc. (SENTRO), Public Services Labor Independent Confederation Foundation, Inc. (PSLINK), and Philippine Medical Association (PMA) (collectively, Pimentel III, et al.) filed the Petition for Certiorari and Prohibition (with Application for Status Quo Ante Order, Temporary Restraining Order (TRO), and/or Writ of Preliminary Injunction)31 against respondents House of Representatives, Senate of the Philippines, Secretary Recto, Executive Secretary Lucas P. Bersamin (Executive Secretary Bersamin) (collectively, respondents), and PhilHealth. They seek to declare as unconstitutional Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular No. 003-2024 on the following grounds:

First, Special Provision 1(d) is a prohibited rider violative of Article VI, Section 25(2) of the Constitution because it is not germane to the 2024 GAA. Specifically, it does not meet the requirements for germaneness, i.e., the provision or clause must be particular, unambiguous, and appropriate. Special Provision 1(d) is inappropriate insofar as it amends the UHCA and Section 8 of Republic Act No. 10351, as amended by Section 14 of Republic Act No. 11346 and Section 9 of Republic Act No. 11467 (the Sin Tax Laws), by diverting funds for the exclusive use of PhilHealth to the National Treasury. It is also ambiguous because its implementation requires reference to previous budget and non-budget legislation.32

Second, the insertion of Special Provision 1(d) exceeds the power of the Congress to appropriate funds under the Constitution as it effectively diverts, for further appropriation by the Executive, the “reserve funds” of PhilHealth earmarked for the implementation of the UHCA.33

Third, for the same reason, DOF Circular No. 003-2024 violates Article VI, Section 29(3) of the Constitution, prohibiting the transfer of special funds to purposes other than for which those funds have been created.34

Fourth, DOF Circular No. 003-2024 further violates Section 70 of Republic Act No. 11936 or the GAA of 2023 (2023 GAA) since even before the end of Fiscal Year December 31, 2024, it already ordered the return to the National Treasury of supposed unused or excess funds of GOCCs like PhilHealth.35

Finally, Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular No. 003-2024 violate the people’s constitutional right to health by effectively depriving the Filipino people of funds that could increase their access to quality and affordable health care goods and services.36

Petition-in-Intervention

Intervenors Atty. Jose Sonny Matula, President, Federation of Free Workers (FFW-NAGKAISA Labor Coalition); Daniel Edralin, Secretary General, National Union of Workers in Hotel Restaurant and Allied Industries; Renato Magtubo, Chairperson, Partido Manggagawa (PM-NAGKAISA); Julius Cainglet, Co-Convenor, Church-Labor Conference; Grace A. Estrada, President, Pinay Careworkers Transnational; Alfredo Maranan, FFW National Treasurer; Jun Ramirez Mendoza, Union President, Vishay Employees Philippines Union-FFW and National Vice President, FFW; Judy Ann Chan Miranda, Chairperson, Nagkaisa Women Committee and General Secretary, PM-NAGKAISA; Vilma G. Reyes, Union President, De La Salle Medical and Health Sciences Institute Employees Union-FFW and National Board Member, FFW; Rene L. Capito, National President, Alliance of Filipino Workers (AFW); Elija R. San Fernando, National Vice President, National Federation of Labor (NFL); Rene De Mesa Tadle, President, Council of Teachers and Staff of Colleges and Universities of the Philippines; Emerito C. Gonzales, Union President, University of Santo Tomas (UST) Faculty Union; Dennis Gutierrez, Union President, Interphil Laboratories Employees Union-FFW; Rolando Librojo, Convenor, Kilusang Artikulo 13; and Atty. Danilo C. Isiderio, FFW Legal Center (collectively, Atty. Matula et. al) moved to intervene in G.R. No. 274778.37

They did so in their respective capacities as national officers and representatives of the NAGKAISA Labor Coalition and in their individual capacities as citizens, taxpayers, and members of PhilHealth.38 They claim to possess vested interests in protecting the funds entrusted to PhilHealth because they will be adversely affected by Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular No. 003-2024, which reduced the “reserve funds” of PhilHealth intended for the expansion of the basic health benefits and services under the NHIP.39

Atty. Matula et al. join the arguments of Pimentel III et al.,⁴⁰ and in addition, submit that:

First, under the Constitution, it is the President, not the Congress, who may be authorized by law to augment an item in the general appropriations law from savings coming from another item.⁴¹ Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular 003-2024 thus unduly delegated to the Secretary of Finance the power to transfer the savings of GOCCs to the National Treasury.

Second, the transfer of idle or unused funds from PhilHealth to the National Treasury constitutes technical malversation of public funds and plunder. The PHP 89.9 billion fund balance belongs to PhilHealth members and is not intended to augment the funds in the National Treasury.42

G.R. No. 275405

Petitioners BAYAN MUNA Chairman Neri J. Colmenares, BAYAN MUNA Vice Chairman Teodoro A. Casiño, BAYAN MUNA Executive Vice President Carlos Isagani T. Zarate, and Former BAYAN MUNA Representative Ferdinand R. Gaite (collectively, Atty. Colmenares et al.) filed the Petition for Certiorari and Prohibition⁴³ against respondents President Marcos, Jr., Executive Secretary Bersamin, the Senate of the Philippines, and the House of Representatives.

Procedurally, Atty. Colmenares et al. argue that their direct resort to the Court is proper since their Petition raises pure questions of law and important constitutional issues.Too, as citizen-taxpayers, they have legal standing to assail the use of public funds through the subject provision of the 2024 GAA. Further, their Petition was filed at the earliest opportunity, i.e., during the lifetime of the 2024 GAA. Finally, the constitutionality of the actions of President Marcos, Jr. and both Houses of Congress is the very lis mota of the case.44

As for the substantive issues, Atty. Colmenares et al. aver that:

First, the President committed grave abuse of discretion in certifying as urgent House Bill No. 8980 sans any public calamity or emergency in violation of Section 26(2), Article VI of the Constitution. The President certified as urgent House Bill No. 8980 “in order to address the need to maintain continuous government operations following the end of the current fiscal year.” This reason, however, did not justify the certification of urgency because no public calamity or emergency existed at that time.

Another, the presidential certification infringes on the constitutional power and duty of the Congress to deliberate on a bill in three readings on separate days before voting thereon. The presidential certification does not excuse compliance with the constitutional requirement that printed copies of a bill be distributed to members of the Congress before it is subjected to a vote for approval.⁴⁶ By virtue of such unconstitutional certification, the Congress undertook a short-cut method in enacting the 2024 GAA.

There was no point in rushing the passage of the 2024 GAA as early as September 2023 as it would not be taking effect until January 1, 2024. At any rate, Article VI, Section 25(7) of the Constitution governs in the event the Congress fails to pass a general appropriations bill for the ensuing fiscal year, i.e., the general appropriations law for the preceding fiscal year shall be deemed re-enacted and remain in force until the corresponding general appropriations bill is passed by the Congress.⁴⁷

Second, the constitutional prohibition against increasing the appropriations recommended by the President was violated. The Report of the BCC inserted a total of PHP 449.5 billion under unprogrammed appropriations resulting in the increase thereof from PHP 289.1 billion to PHP 731.4 billion, which is void for being substantially different from the amount contained in the NEP submitted by the President to the Congress.⁴⁸

Third, increasing the unprogrammed appropriations and inserting the subject provision as a new item not found in the version of House Bill No. 8980 approved by both Houses of Congress are unconstitutional since the BCC is not a third house of the Congress; it is not empowered to perform legislative functions. If anything, the power of the BCC is only to harmonize the differences between the bills passed by each Chamber of Congress. Thus, when there is no discrepancy, there is nothing to harmonize in the bill, as here.49

Finally, Atty. Colmenares et al. pray that the Court issue guidelines on the exercise of the President’s power to certify a bill as urgent.⁵⁰ They also seek the issuance of parameters for the creation, practice, and process of a bicameral conference committee in accordance with the Constitution.50

G.R. No. 276233

Petitioners 1Sambayan Coalition; Members of U.P. Law Class 1975 namely, Jose P.O. Aliling IV, Augusto H. Baculio, Edgardo R. Balbin, Antonio T. Carpio, Jr., Richard J. Gordon, Oscar L. Karaan, Benjamin L. Kalaw, Lucas C. Licerio, Tomas N. Prado, Elizer A. Odulio, Aurora A. Santiago, Emily Sibulo-Hayudini, Conrad D. Soriano, Mercy Pine, Prudencio B. Jalandoni, Nonette C. Mina, and Jose B. Tomimbang; Former Ombudsman Conchita Caprio-Morales; Senior For Seniors Association, Inc., represented by Ms. Carol Blanco Benavides; Kidney Foundation of the Philippines, represented by Jose Rafael Hernandez; Atty. Christopher John P. Lao; the San Beda College Alabang-Human Rights Center namely, Gloriette Marie Abundo, Elvie Amiscosa, Isabel Francesca Anunciacion, Aramaine Balon, Charmae Ann Maravilla, and Rhiana Isabelle Navarro (collectively, 1Sambayan Coalition et al.) filed the Petition for Certiorari and Prohibition (with Urgent Prayer for the Issuance of a TRO, Writ of Preliminary Injunction and/or Other Injunctive Remedies)51 dated October 16, 2024 against the same respondents.

1Sambayan Coalition et al. argue that the subject provision is an invalid delegation of authority as the power to transfer savings is only vested upon those enumerated in the exhaustive list under Article VI, Section 25(5) of the Constitution, of which the Congress is not a part.⁵² Nonetheless, even if the transfer was authorized by the President himself, it would still constitute a transfer of special funds raised for a specific purpose, violative of Article VI, Section 26(3) of the Constitution.⁵³

Too, 1Sambayan Coalition et al. argue that in issuing DOF Circular No. 003-2024, the Secretary of Finance arrogated unto himself the authority belonging to the President under Article VI, Section 25(5) of the Constitution.⁵⁴ They also urge the Court to find the DOF Secretary liable for malversation and/or plunder for issuing the directive to transfer PhilHealth funds to the National Treasury.

Comments on the Petitions

The Office of the Solicitor General (OSG),⁵⁵ on behalf of respondents House of Representatives, the DOF, Secretary Recto, and Executive Secretary Bersamin pray for the dismissal of the Petitions allegedly because:

First, the requisites for the exercise of judicial review are absent.

Second, there was violation of the doctrine of exhaustion of administrative remedies which include the filing of a case before the DOF itself.

Third, the President was improperly impleaded and must be dropped as a respondent by virtue of his presidential immunity from suit.⁵⁶

Fourth, Special Provision 1(d) is not a rider because it has a reasonable relation to the 2024 GAA where sources of funds for unprogrammed appropriations are necessarily included. It does not amend or repeal any provision of the UHCA and the Sin Tax Laws because: (1) the concept of “fund balance” under Special Provision 1(d) is different from the concept of “reserve funds” under the UHCA; (2) the concept of “reserve funds” remains the same even after the 2024 GAA containing the special provision took effect; (3) it does not revoke the mandate of PhilHealth under the UHCA; (3) the special provision does not authorize the withdrawal of the Investment Reserve Fund of PhilHealth; (4) the prohibition against the transfer of PhilHealth’s reserve fund to the general fund remains in place; and (5) the subject matter of the Sin Tax Laws is different from the subject matter of the special provision.

Fifth, fund balance is not the same as savings which, in the context of Section 25(5), Article VI of the Constitution, pertains to “money originally appropriated for one purpose [but] remain unspent after that purpose has been fulfilled or otherwise terminated.”⁵⁷ Thus, Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular No. 003-2024, as well the DOF Secretary’s directive to transfer the fund balance to the National Treasury did not emanate from the power of the President to transfer savings under Article VI, Section 25(5) of the Constitution. There is therefore no undue delegation of power to the DOF.⁵⁸

Sixth, there is no violation of the right to health.⁵⁹ The out-of-pocket expenditure of the people for healthcare has no relation to the remittance of PhilHealth funds to the National Treasury.⁵⁹ The remittance will not necessarily hamper or disable the implementation of the UHCA.⁵⁹ Besides, the issue on the benefit packages of PhilHealth is a question of policy beyond the jurisdiction of the Court.

Seventh, the fund balance defined under DOF Circular No. 003-2024 does not include the special fund from sin tax collections as the fund balance can only include “unrestricted funds,” hence, there is no occasion by which Article VI, Section 29(1) of the Constitution could have been violated.

Eighth, there is no violation of the cash-budgeting system under Section 70 of the 2023 GAA. The cash-budgeting system only requires that unutilized amounts remaining at the end of the fiscal year must be returned to the National Treasury. It does not require the reversion of the unexpended balances of appropriation to be made only at the end of the fiscal year.⁶⁰

Ninth, the transfer of funds from PhilHealth to the National Treasury does not constitute technical malversation or plunder. One element of technical malversation is the application of the subject funds to a purpose different from that for which they were originally appropriated by law. The fund balance of PhilHealth, however, was not appropriated by law for a specific purpose, hence, is not a special fund. Rather, it comprises the “unexpended” or “unutilized” subsidy contributions of the National Government to PhilHealth. On the other hand, the gravamen of plunder is the accumulation of ill-gotten wealth through a combination or series of criminal acts. Here, the fund balance of PhilHealth was clearly remitted to the National Treasury, thus, there was no acquisition of ill-gotten wealth to speak of either.62

Tenth, the President’s certification of House Bill No. 8980 is in accordance with Article VI, Section 26(2) of the Constitution.⁶⁴ A general appropriations law is not different from any ordinary statute and must be passed promptly. The timely passage of a general appropriations law ensures that the National Government’s planned programs and projects within a particular fiscal year are realized;⁶⁴ and provides a degree of stability and predictability essential to the nation’s economic growth and development.62

Recognizing the importance of the timely passage of the 2024 GAA, the President certified as urgent House Bill No. 8980. If the 2024 GAA were not passed by December 31, 2023, the 2023 GAA would have been deemed re-enacted. This would have resulted in the government’s inability to address its specific priorities, goals, and needs for the 2024 Fiscal Year. Notably, the Congress itself did not question the President’s certification of House Bill No. 8980, hence, the same must be given due deference as a valid exercise of wisdom by the Chief Executive.63

Regarding the required distribution of printed copies of House Bill No. 8980 in advance, Tolentino v. Secretary of Finance⁶⁵ has long settled that the President’s certification for immediate enactment of a bill dispenses not only with the required reading on three separate days but also the required printing and distribution of printed copies in advance; otherwise, the time saved would be so negligible as to be of any use in ensuring the immediate enactment of the “urgent” bill.⁶⁶

Eleventh, What Article VII, Section 22 of the Constitution prohibits is the increase in the President’s proposed budget or the BESF;⁶⁷ and not the increase in the unprogrammed appropriations which is in accordance with Article VI, Section 25(1) of the Constitution.

It is customary that the President submits to the Congress the following budget documents: (1) Budget Message; (2) BESF; (3) NEP; and (4) Staffing Summary. Of these documents, the BESF is the constitutionally and statutorily mandated document bearing the President’s proposed budget for the ensuing fiscal year. Notably, unprogrammed appropriations are not part of the National Government Expenditures in the BESF. On the other hand, the NEP, which contains unprogrammed appropriations, does not reflect the sources of financing mandated by Article VII, Section 22 of the Constitution.⁶⁷ Therefore, since Congress did not increase the budget proposed by President Marcos, Jr. in the BESF, there is no violation of Article VI, Section 25(1) of the Constitution.⁶⁷

Twelfth, the BCC has the power to modify and add provisions to a bill under its review.⁶⁸ The rules of both Houses of Congress in fact recognize this power. Further, Tolentino confirmed the BCC’s power to propose amendments and even include an entirely new provision that is not found either in the House bill or in the Senate bill.⁶⁸

Lastly, the Court may not make any finding of criminal liability for technical malversation and/or plunder against the DOF Secretary in a petition for certiorari and prohibition.⁶⁹

For its part, PhilHealth, through the Office of the Government Corporate Counsel (OGCC) headed by Government Corporate Counsel Solomon M. Hermosura, asserts that DOF Circular No. 003-2024 complied with the guidelines set by the 2024 GAA. The enforcement of the national budget is vested upon the executive branch and the DOF is primarily responsible for the efficient management and financial resources of the government. It also echoes the OSG’s argument that the fund balance does not include special funds under Article VI, Section 29(3) of the Constitution since it only covers unrestricted funds. Assuming arguendo that the fund balance is considered a special fund, the purpose for which it was created had already been fulfilled or abandoned.⁷⁰

PhilHealth likewise argues that Special Provision 1(d) is not a rider and is germane to the purpose of the GAA, which is the allocation of funds for the operation and activities of the government. It simply bears the mechanism by which a source of funding for unprogrammed appropriations under the GAA is created.

Finally, PhilHealth states that the cash-budgeting system under Section 70 of the 2023 GAA does not require the government subsidy to be utilized in full by December 31, 2024. There is also no prohibition against reversion of the unutilized funds prior to December 31, 2024.

Consolidation of cases and Preliminary Conference

By Resolution71 dated September 9, 2024, the Court ordered the consolidation of G.R. No. 275405 with G.R. No. 274778 and set the consolidated cases for oral arguments on January 14, 2025. Meanwhile, under Resolution72 dated October 8, 2024, the Court granted the Motion for Intervention with Leave of Court73 filed by Atty. Matula, et al.; and under Resolution74 dated October 29, 2025, the Court ordered the consolidation of G.R. No. 276233 with G.R. Nos. 274778 and 275405.

The Court thereafter held a preliminary conference on the consolidated cases on October 9, 2024, during which, petitioners were directed to file their respective compliances with the Court’s directive to submit proofs of their respective legal standing and/or authorization to file the Petitions;⁷⁷ their responses to the queries of the Court;75 the specific documents pertaining to the fiscal operations of PhilHealth;76 and the names and curriculum vitae of their proposed amici curiae.77

TRO and Compliances

Under Resolution78 dated October 29, 2025, the Court issued a TRO against the transfer to the National Treasury of the remaining PHP 29.9 billion PhilHealth funds; and the further implementation of Special Provision 1(d) and DOF Circular No. 003-2024.

The parties also submitted their responses to the clarifications sought by the Court on several matters. Petitioners maintain79 that the DOF mistakenly deducted the benefit claims of indirect members from their premium contributions and labeled the difference as “excess funds,” which may be transferred to the National Treasury. They argue that this difference still makes up the premiums of members that may not be taken by the DOF. Thus, allowing the transfer of this balance breaches the nature of PhilHealth as a public insurer that pools member contributions in order to insure against risks. These pooled contributions are held by PhilHealth in trust for its members to be used in the future should any of the insured risks, i.e., illnesses and other health-related concerns, occur.80

Petitioners reiterate their prayer for the issuance of a status quo ante order, emphasizing that though the Court may later on order the return of the transferred amount, the huge amount to be paid back to PhilHealth would require appropriations by Congress in future national appropriations statutes. Meantime, people suffer opportunity cost for this delay because PhilHealth would be giving up the value of foregone benefits that it could have otherwise immediately provided to all its members.81

Petitioners emphasize that as of December 31, 2024, the balance sheet of PhilHealth reflected PHP 1.25 trillion as total liabilities, which significantly exceeds its total assets of PHP 588.5 billion, meaning, PhilHealth was already incurring a total negative equity position of PHP 663.7 billion. Petitioners argue that this negative income and negative capital of PhilHealth is inconsistent with the assertion of the DOF that PhilHealth has excess funds82 as PhilHealth is balance sheet insolvent. Petitioners predict that if PhilHealth would not adjust its policies or if the government were to cease appropriating funds to address PhilHealth’s reserve gaps, PhilHealth’s insolvency would lead to bankruptcy.83 Petitioners assert that the DOF did not consider the Provision for Insurance Contract Liabilities (ICL) in computing the fund balance of PhilHealth.84

Petitioners state as well that based on the financial statements of PhilHealth in previous years, all unused portions of its income were transferred and considered “reserve funds,” which could not be utilized for purposes other than those under Section 11 of the UHCA.85

Atty. Matula et al. submit that if PhilHealth does not have enough assets to cover the Provision for ICL, PhilHealth would be unable to fund the claims of both direct and indirect contributors, let alone, sustain their insurance operations. They further note that as of March 31, 2024, PhilHealth had PHP 1.251 trillion contingent liabilities including pending hospital claims.86

PhilHealth, for its part clarifies that: (1) the PHP 89.9 billion fund balance of PhilHealth was intended to be remitted to the National Treasury in four tranches, viz.:88

Particulars Amount Date of Remittance 1st Tranche 20.0 B May 10, 2024 2nd Tranche 10.0 B August 21, 2024 3rd Tranche 30.0 B October 16, 2024 4th Tranche 29.9 B November 20, 2024 Total 89.9 B

(2) PhilHealth is an attached agency of the DOH; (3) all Filipinos are automatically included in the NHIP; (4) PhilHealth Board Resolution No. 2899, Series of 2024, already increased the NHIP benefit package by 30%; (5) the sources of PhilHealth funds include those enumerated under Sections 11 and 37 of the UHCA; (6) the premium subsidy for indirect contributors is included annually in the GAA; (7) PhilHealth adopts the “one fund concept”, i.e., a general fund that is generally available to carry out all functions and activities of PhilHealth, regardless of source; and (8) premium contributions from direct contributors are recognized under “Members’ Contributions – Direct Contributor” while premium contributions of indirect contributions in the form of government subsidies are recognized under “Members’ Contribution – Indirect Contribution.”⁸⁹

PhilHealth admits that some of their notable liabilities are Financial Liabilities, 95% of which pertains to Accrued Benefit Payables (i.e., claims in process at a given period), and Provision for Health Benefits (i.e., benefit claims already incurred but still in the possession of the health facilities and have yet to be submitted to PhilHealth). PhilHealth explains that the insufficiency of assets to cover the Provision for ICL means that the current contribution scheme of PhilHealth is insufficient to sustain the benefits and administration of the benefits availment of members in the future.⁹⁰

Even then, PhilHealth maintains that the fund balance transfer is not part of the “reserve funds” referred to under Section 11 of the UHCA.⁹¹ None of its “reserve funds” or unused portion thereof is currently invested. It employs a laddering strategy in the investment of the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) to ensure that there are steady maturities occurring over a period of time. The cash flow streams from its investments are the main source of PhilHealth funding. After deducting its daily funding requirements, the remaining net investible funds are reinvested by PhilHealth. For 2023, PhilHealth’s investment portfolio stood at PHP 498.3 billion and earned PHP 20.7 billion. As of June 30, 2024, its investment portfolio was valued at PHP 504 billion with PHP 12.9 billion earnings.⁹²

The OSG, on the other hand, explains93 that PhilHealth is an attached agency of the DOH. PhilHealth delivers individual-based health services, while the DOH is responsible for population-based health services under Sections 17 and 18 of the UHCA,⁹⁴ but no portion of the budget appropriated to the DOH is directed towards the programs of PhilHealth.⁹⁵

The OSG further informs the Court that the fund balance transfer shall be used to fund certain projects and programs under the unprogrammed appropriations of the 2024 GAA, such as:⁹⁶

(1) maintenance, repair, and rehabilitation of infrastructure facilities (routine maintenance of national roads);

(2) the Panay-Guimaras-Negros (PGN) Island Bridges Project;

(3) government counterpart of foreign-assisted projects;

(4) payment of right-of-way;

(5) strengthening assistance for government infrastructure and social programs;

(6) public health emergency benefits and allowance for health care and non-healthcare workers;

(7) management and supervision of peace process;

(8) payment of personnel benefits;

(9) priority social programs for health, social welfare and development, higher education, and technical and vocational education;

(10) revised Armed Forces of the Philippines modernization program;

(11) pension and gratuity fund; and

(12) financial subsidy for purchase of photovoltaic mainstreaming (solar home system) for rural electrification.

The OSG also clarifies that the PhilHealth fund balance, in particular, was computed by deducting the average two-year actual expenditure of PhilHealth in the amount of PHP 280.6 billion from PhilHealth’s accumulated net income of PHP 463.7 billion, leading to the difference of PHP 183.1 billion. The entire sum of PHP 183.1 billion, theoretically, may be transferred to the National Treasury but the DOF exercised prudence by directing PhilHealth to simply return the smaller amount of PHP 89.9 billion, which represents the unutilized government subsidies to PhilHealth from 2021 to 2023:97

In PHP Billions FY 2021 FY 2022 FY 2023 TOTAL Premium for indirect contributors 80.1 80.2 78.8 239.1 Less: Benefit claims for indirect contributors 53.1 56.1 40.0 149.2 Net Flow-Fund Balance 27.1 24.0 38.8 89.9

Here is the cleaned-up text with all footnote markers (e.g., 40^{40}40) converted into plain-number superscripts using proper formatting:

On PhilHealth’s liabilities, the OSG expounds that the Provision for ICL is the difference between the Present Value of Future Outflows (i.e., benefit payments plus administrative expenses) and the Present Value of Future Inflows (i.e., premium collections plus interest earnings). It is not an actual obligation incurred by PhilHealth but an accounting construct to provide an estimate of potential obligations of PhilHealth in the future.